BAN CHIANG

DISCOVERY

In 1966, Stephen Young, son of a former U.S. ambassador to Thailand, was walking through the village of Ban Chiang in northeast Thailand when he tripped on a kapok tree root and fell flat. Under him he felt a ring protruding from the soil, which turned out to be the rim of a partially buried clay pot. He then noticed that he was in fact surrounded by other “rings” in the earth. The pots—slowly being exposed by erosion—were buff in color with striking designs in red. A lost ancient culture was being revealed. That “oops” fall started a chain of events that led to a major archaeological discovery of the 20th century and international awareness of its importance.

BAN CHIANG

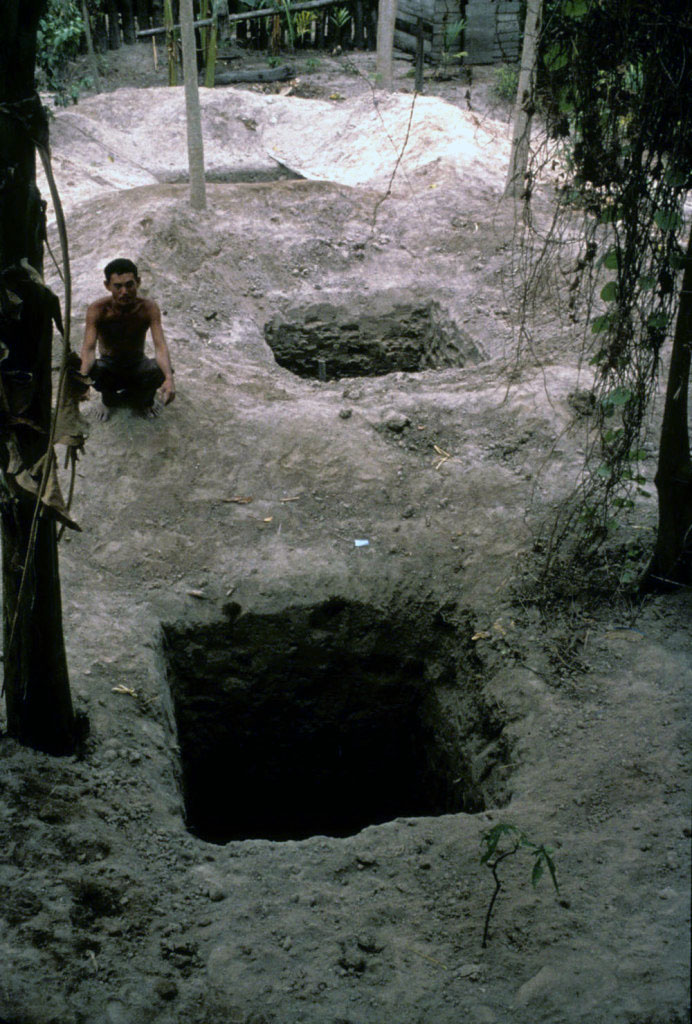

EXCAVATIONS

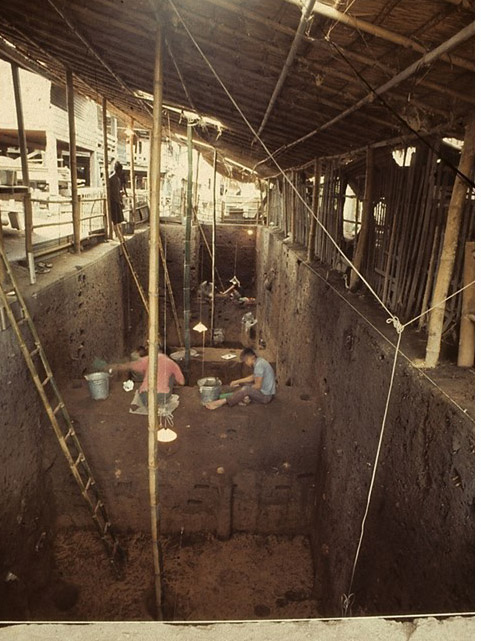

A confluence of just the right interests, timing, and international connections made the Ban Chiang excavations possible.

Both excavation sites were chosen because they were in relatively undisturbed areas near the center of the current-day village mound. It was thought likely that these locations would yield the site’s full chronological sequence.

After the excavations, FAD loaned about 6 tons of materials from the site to Penn Museum for analysis. [Most was returned in the 1980s, and some materials are still under study.] Skeletal remains went to the University of Hawaii and the University of Otago (New Zealand) received the faunal remains. After the death of Dr. Gorman in 1981, Penn Museum named Joyce White the Ban Chiang Project director.

Today Dr. White continues to direct the analysis and publication of the Ban Chiang excavations via the Institute for Southeast Asian Archaeology (ISEAA) and as a consulting scholar to the Penn Museum.

BAN CHIANG'S WILD GINGER MAN

CHET GORMAN

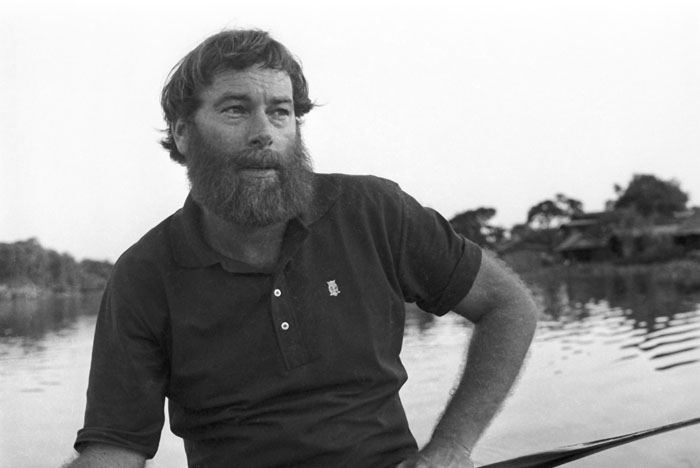

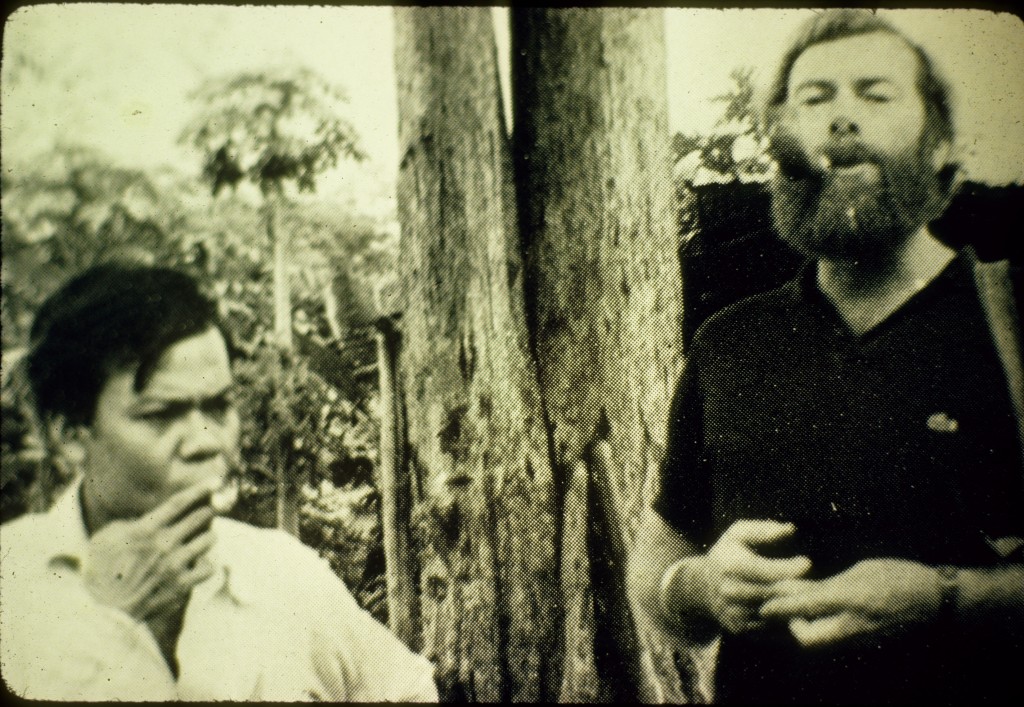

It’s been more than thirty years since Chet Gorman died. He is unmistakable in his photographs with his blazing red beard, often wearing florid Hawaiian shirts and with his big cigar cocked at a jaunty angle—the image of a pioneering and romantic archaeologist. Shortly after Chet’s death in 1981, his co-director Pisit Charoenwongsa (Fine Arts Department of Thailand) described him as “…larger than life. A man of immense charisma, energy, charm, and humor, he formed lasting friendships with incredible ease. He was at home under any circumstances, from a bamboo shelter in the jungle to a Philadelphia cocktail party.”

Chet was born in Oakland, California. He grew up on his parent’s dairy farm in Elk Grove, California. His undergraduate degree in Anthropology came from Sacramento State College in 1961 and his Ph.D. from the University of Hawai’i under the guidance of Dr. Wilhelm Solheim. Solheim sent Chet to Thailand for the first time in 1963-64, where he discovered the site of Non Nok Tha. In 1965-66, he was in Thailand for his doctoral research, when his focus shifted from the plains to the Thai hills along the Burmese border and he found Spirit Cave (see map below). The professionalism and sensitivity with which Chet conducted the Spirit Cave excavation earned him international renown among archaeologists as well as respect from the Thai archaeology community. His ability to speak Thai also won him friends there: he was fluent enough to give public lectures and participate in debates in Thailand, and to give interviews in Thai to Thai reporters.

In early 1973, during a break in the excavations of Spirit Cave, Chet made a contact that would prove to be a major turning point in his career. Froelich (Fro) Rainey, then director of the Penn Museum, recruited him to be the Museum’s representative for a large-scale investigation at the site of Ban Chiang in northern northeast Thailand.

Many aspects of the excavations at Ban Chiang were cutting edge for the time. Long-time Penn Museum volunteer John Hastings remembers: “Back in 1973, Chet had tremendous foresight regarding the role that computers would be playing in archaeological research. He designed the excavation and artifact recording system from the beginning to be computerized, one of the first excavations probably in the world with this objective. The bag log and small find log numbering and recording systems were very computer-friendly. Moreover, Chet had all the materials recovered from the dig lent to the University Museum for analysis so that detailed measurements and observations could be systematically recorded and preserved in computer databases. In those days the data were fed into a mainframe computer on IBM punch cards and recorded on rolls of magnetic tape, and the programming was also done with punch cards.”

Dr. Joyce White, director of the Ban Chiang Project since 1981, recalls that when she was a first year graduate student at Penn, she walked into Chet’s office to declare her intention to become a Southeast Asian archaeologist, and to ask Chet to be her advisor. The response he gave is hard to believe four decades later, “I don’t want any female graduate students,” was his answer. But she persevered and became Chet’s only female student at Penn. In Joyce’s words, “Chet’s students were more apprentices than advisees. Our education consisted less of being lectured at in a classroom, and more of the opportunity not only to observe, but to participate in the life of a scholar. We were instructed in how to be professional anthropologists.”

If Chet became the subject of a conversation, it was sure to lead to a colorful story. One such story involved Chet, a woman named Carobel, and a distinctively shaped Ban Chiang pot. It ends in a way that could only be Chet. In 1977, Chet was giving a talk to a Ceramics Society in Hong Kong where he was showing slides of Ban Chiang pottery. As he was going through all the different pottery types—a beaker, a globular cord-marked, a white carinated—he came upon a particular pot in the slideshow which hadn’t been assigned a name yet. A woman named Carobel, whom he had met briefly before, inquired from the audience, “Chet, what’s the name of that pot?” To which Chet responded, “Why, it’s a Carobel pot.” And the woman asked, “Oh! Why is it a Carobel pot?” To which Chet replied, “Because it has a nice round bottom just like Carobel.” Chet recounted the story to Joyce when he returned to Philadelphia. Years later in 1982 when Joyce was writing the catalogue for the Smithsonian’s travelling exhibition Ban Chiang: Discovery of a Lost Bronze Age, she had to give a name to the pot, which appears on page 69. Not knowing the spelling of Carobel’s name, Joyce termed it a “Carabel Type” pot. Years later in the 1990s, Joyce met Carobel and a mutual friend for lunch in Manhattan and the story was retold. Far from being offended by Chet’s comment, Carobel thought it was one of the highlights of her life and she wanted the story to be told at her funeral.

Chet’s life ended tragically on June 7th, 1981 when he died after a long bout with melanoma.

At a tribute to Chet shortly after his death, Pisit Charoenwongsa said, “The tragedy of his death was that all this was cut short. But he did at least leave behind him a solid body of academic achievement, the respect and admiration of the Thai people, and a legacy of memories in the minds of his hundreds of friends that will not disappear. It was a life to be proud of. Chet never talked about an epitaph, but one he would have liked is based on J. P. Donleavy’s character, one of Chet’s favorites: God’s mercy on the wild Ginger Man.”

BAN CHIANG

SIGNIFICANCE

The discovery and excavation of Ban Chiang was a major milestone in our understanding of Southeast Asian prehistory.

Scientific archaeology came late to Southeast Asia, due to decades of war and political unrest that limited access to much of this region and held back international collaboration and resource-sharing. Until Ban Chiang excavation and that of another site, Non Nok Tha, scholars thought that Southeast Asia had always been a passive recipient of cultural ideas from India and China. In particular, they thought that bronze metallurgy—the making of bronze alloy and bronze artifacts—was associated with complex and socially stratified societies and that this technology spread to Southeast Asia no earlier than about 500 B.C.

Read more:

“The Transmission of Early Bronze Technology to Thailand: New Perspectives”, by Joyce C. White and Elizabeth G. Hamilton.

“Distinctive Bronze Age for the Ban Chiang Cultural Tradition.”

BAN CHIANG

FAME

Events spanning four decades have brought international fame to Ban Chiang.

Ban Chiang first made Thai news when rampant looting sparked countermeasures to preserve the archaeological site. In 1971, publication of an erroneous thermoluminescence date (4630 B.C.) for one of the famous Ban Chiang pots came to the attention of antiquities collectors—creating a spike in demand for the pots. Extensive looting ensued and threatened to erase evidence of the ancient Ban Chiang cultural tradition before it could be studied. Countless incomplete pots and ceramic sherds were tossed aside in the frenzy to pull whole pots out of the ground. In Bangkok’s Sunday Morning Market, huge numbers of unprovenienced Ban Chiang pots (and eventually fakes) were suddenly for sale.

In response, King Bhumibol of Thailand visited Ban Chiang in 1972 to fact-find and to urge more inclusion of villagers to help preserve Thai cultural heritage. Expanding on a 1961 law that prohibited export of ancient artifacts without permission from the Fine Arts Department (FAD), a new Thai law enacted after his visit made it specifically illegal for any Ban Chiang artifact to be sold, bought, or exported from Thailand without permission from FAD.

The Western press brought Ban Chiang to early international fame. In the mid-1970s the New York Times and other western media got excited when an early date of 3600 B.C. (later proven erroneous) was published for bronze artifacts from the Penn/FAD excavations. The Washington Post’s political op-ed writer, Joseph Alsop, devoted a column entitled “Rewriting Human History” (1975) that pondered the idea that Ban Chiang bronze dating could completely upend then-current assumptions about the progression of “Civilization” and bronze-making in Southeast Asia. William Honan of The New York Times wrote a feature “The Case of the Hot Pots: An Archaeological Thriller” (1975) that talked about the beginning of the race between scholarship and looting in uncovering the ancient past of Ban Chiang and northeast Thailand.

From 1982-86 the traveling exhibit Ban Chiang, Discovery of a Lost Bronze Age brought scientific findings about Ban Chiang to the general public.

Curated by Joyce White, this Smithsonian-produced exhibit traveled to 12 U.S. and international venues, before installation as one of the permanent exhibits in the Ban Chiang National Museum in Thailand in 1987.

In 1992, Ban Chiang became a UNESCO World Heritage Site, based on the criterion that it “bears unique or at least exceptional testimony to a civilization that has disappeared.”

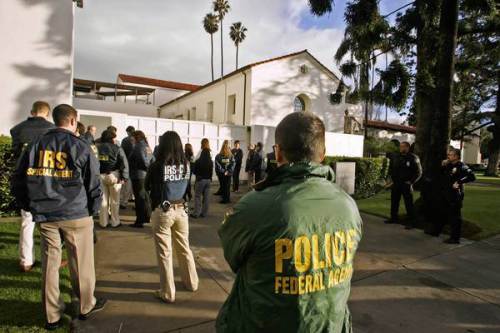

Recent events have raised public awareness about smugglers and illegal collectors of Ban Chiang artifacts.

Ban Chiang again came into front-page news in January 2008, when 500 law enforcement officers raided several U.S. museums and businesses that had large holdings of Ban Chiang and other prehistoric artifacts from Thailand. Investigations determined there was no documentation that artifacts had been legally exported. As the legal case slowly unfolded, institutions began to return artifacts to Thailand in 2014.

Read the Bangkok Post article, “Ancient artefacts back where they belong” (2014)

For more in-depth information, click here.

ISEAA is a program partner of the Urban Affairs Coalition (UAC), a nonprofit 501c3 entity. UAC administers funds raised by ISEAA, thus freeing us to focus on research and publication.