ISEAA

METALS MONOGRAPH

Our new Metals monograph applies current archaeological perspectives to interpret metals and metals-related evidence from Ban Chiang and three other sites.

The discovery of the bronze age culture of Ban Chiang changed views about the technological sophistication of prehistoric Southeast Asia. Before the 1970s, Southeast Asia was considered a technological backwater. The prevailing scholarly opinion held that the earliest metal use in Southeast Asia was no older than ca. 500 B.C.

But the 1974 and 1975 excavations at Ban Chiang—as well as survey and excavations at Non Nok Tha, Ban Phak Top, Ban Tong, and Don Klang—demonstrated that Southeast Asia did have sophisticated metallurgy as early as the first half of the 2nd millennium B.C. This is over a thousand years earlier than was previously suspected. Another surprise was that this timeframe was long before there were traces, in the archaeological record of the area, of any societies more complex than simple egalitarian villages.

Using current archaeological perspectives to interpret the prehistoric bronze technology of Thailand, Drs. Joyce White and Elizabeth Hamilton have completed the fourth and final volume of a monograph that presents metals and related evidence from four sites in northeast Thailand, Ban Chiang, Ban Tong, Ban Phak Top, and Don Klang. The monograph ll includes a history of viewpoints about the social place of early bronze technology, current evidence for its varied roles in prehistoric societies, a new paradigm for understanding metals in society, and current methodological approaches for the study of prehistoric metals. This four-volume monograph is the second entry in the Penn Museum Ban Chiang monograph series.

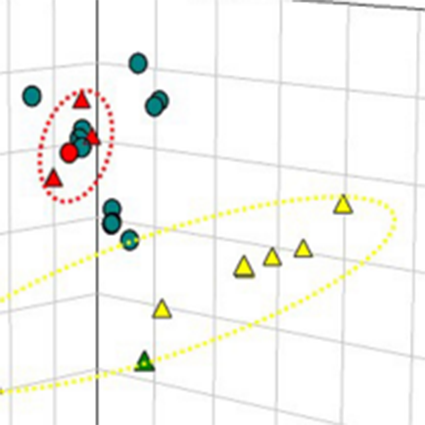

Collaborating scholars include Dr. Vince Pigott on prehistoric copper mining and smelting, Dr. William Vernon on crucibles, and Dr. Oliver Pryce on copper sourcing using lead isotope analysis.

The monograph is organized in four parts:

- A background section on current understanding of metals in prehistoric societies and methods for their study

- Presentation of detailed metal evidence from the four sites, including classification, technical analyses, and excavated contexts

- Discussion of the larger regional context, including a chapter on copper production evidence by Dr. Vincent Pigott

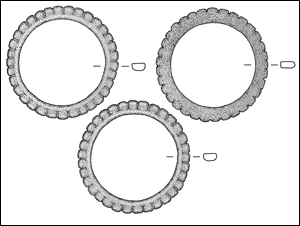

- A detaled catalog of all the contextual and analytical information about the 639 metal objects, five prills, and 102 crucibles and crucible fragments from the four sites, including photomicrographs.

Search metals and metals-related data and images from Ban Chiang, Ban Tong, Ban Phak Top, and Don Klang

BAN CHIANG

CERAMICS ANALYSIS

Modern study of the pottery excavated from Ban Chiang in the 1970s has begun to tell us about the prehistoric social networks and technological communities that produced it.

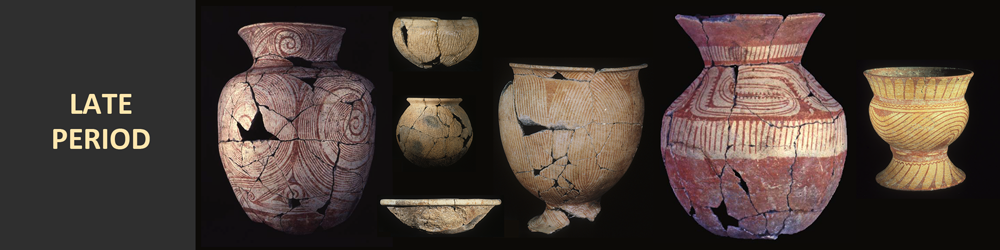

Surface finds of the famous painted red-on-buff pottery first brought archaeologists’ attention to Ban Chiang in the 1960s. The 1970s Thai Fine Arts Department/Penn Museum excavations unearthed more than 400 prehistoric ceramic vessels, revealing a far wider variety of pottery styles that spanned 2100 B.C. to A.D. 200. Through the millennia, the Ban Chiang ceramics show a strong aesthetic tradition, and many vessels may be considered works of art. Utilitarian vessels also abound, sometimes giving evidence of use such as soot from a cooking fire.

Most of the reconstructible or nearly intact pots were grave goods. The ability to study a large group of nearly complete pots from clear social contexts (human burials at Ban Chiang) is a special opportunity for ceramic archaeologists, who often have only sherds to study from other sites.

The study of complete ceramic vessels using modern-day approaches is taking us far beyond classification of the shapes and decorations of pots, to reveal much about ancient social groups and ceramic technologies at Ban Chiang and in the region.

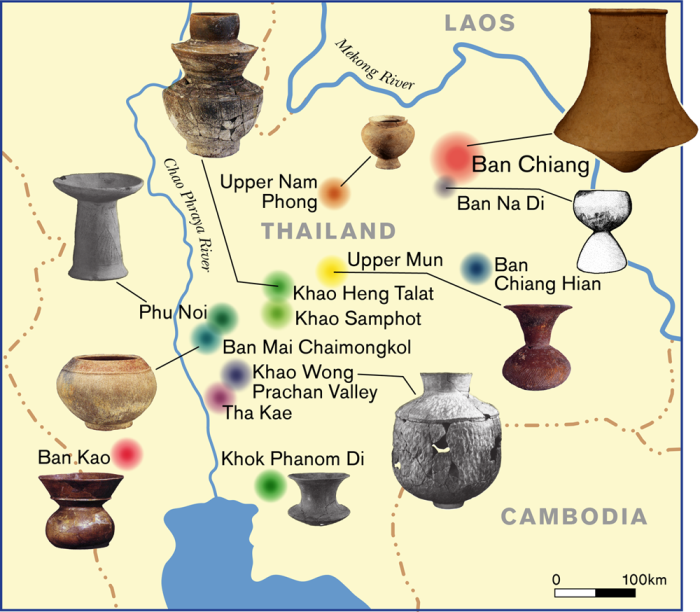

Of outstanding note is that distinctive prehistoric ceramic traditions in Thailand were practiced in limited geographic areas. Pottery styles could be different within 25 kilometers (15 miles) of each other…even within the same time period. Other archaeological evidence—e.g. similarities of shell and metal artifacts—shows that there was interaction among these areas, so it was not a matter of physical or social isolation that led to different traditions. Instead, it is as if distinctive pottery styles were used to signal identity of a village or group of villages.

Read more about related publications from pilot studies of Ban Chiang ceramics:

Glanzman, W.D., and S.J. Fleming

1985 Ceramic technology at prehistoric Ban Chiang, Thailand: fabrication methods. MASCA Journal 3(4):114-121.

McGovern, P.E.

1986 Ancient ceramic technology and stylistic change: contrasting studies from Southwest and Southeast Asia. In Technology and Style, edited by W.D. Kingery, pp. 33-52. Ceramics and Civilization Vol. 2. American Ceramic Society, Columbus, OH.

McGovern, P.E., W.V. William , and J.C. White

1985 Ceramic technology at prehistoric Ban Chiang, Thailand: physiochemical analyses. MASCA Journal 3(4):104-113.

White, J. C., W. V. William, S. J. Fleming, W. D. Glanzman, R. G. V. Hancock, and A. Pelcin

1991 Preliminary cultural implications from initial studies of the ceramic technology at Ban Chiang. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association 11:188-203.

Yen, Douglas

1982 Ban Chiang pottery and rice: a discussion of the inclusions in the pottery matrix. Expedition 24(4):51-64.

ISEAA

DOCUMENTING EXCAVATED POTS

Documenting the physical characteristics of the ceramics and the social contexts where they were found (mostly graves) was the first step toward understanding the ceramic traditions of prehistoric Ban Chiang.

Documentation of Ban Chiang pots in situ yielded a rich dataset that would not have been possible had pots been removed from the site by looters or untrained excavators before study.

Precise locations of pots and pot sherds were recorded at the sites excavated in 1974 and 1975. Tens of thousands of site images—black and white photos and Kodachrome slides—recorded excavation contexts, artifacts in situ and the progress of the excavations. Measurement of multiple excavation levels and their contents were documented in hundreds of field drawings.

In early 1976, thousands of bags of sherds and pots, carefully labelled as to provenience, arrived at the Penn Museum for study. There they were painstakingly reconstructed as pots during more than two decades of work by trained volunteers and Penn work-study students.

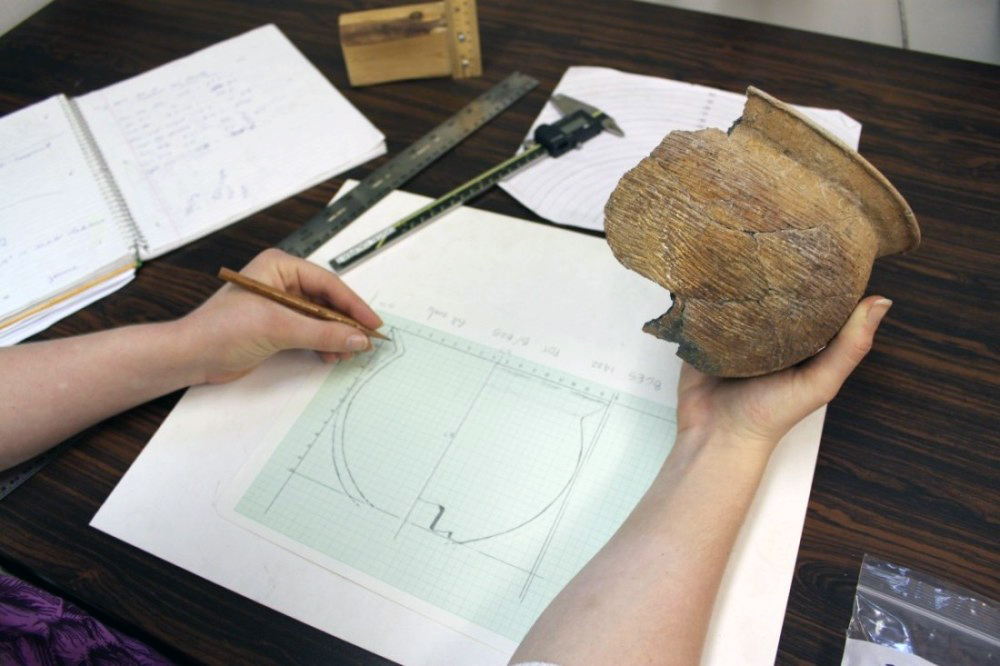

Over that same two decades, pots were documented with carefully measured drawings, involving the skill of many illustrators. Most were Penn work-study students trained in the Ban Chiang lab.

To date, about 500 complete and reconstructed pots from Ban Chiang and three related sites—Ban Tong, Ban Phak Top, and Don Klang—have been photographed and digitally archived.

The Ban Chiang Project began to computerize site and artifact documentation in the late 1970s using mainframe computing. In the mid-2000s, digitization of images and other records began and the process is still underway today.

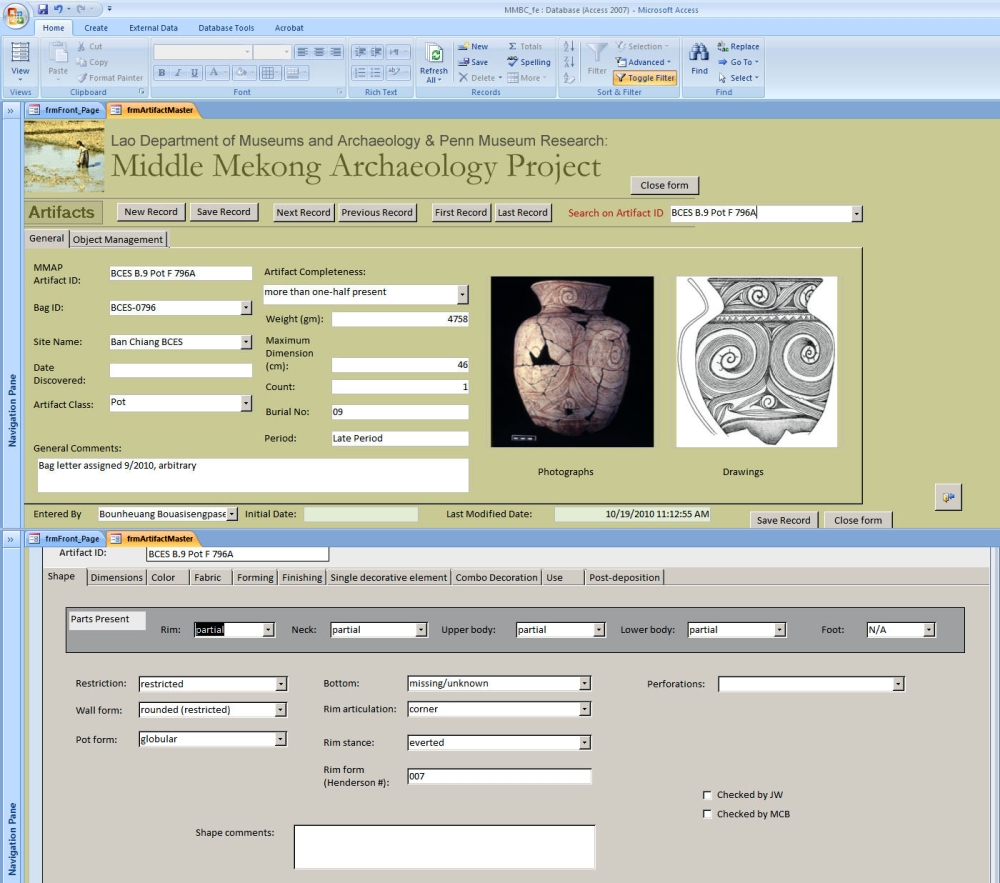

During the Ban Chiang Year of Ceramics, a comprehensive ceramics database was developed for the ceramics of Ban Chiang and three related sites. Under the direction of Dr. Marie-Claude Boileau, more than 130 variables on each of the 500 whole and reconstructed pots were recorded during academic year 2010-2011 and through 2012. Detailed and systematic data such as pot shape, dimensions, color, fabric, as well as forming and finishing techniques became part of the digital record.

BAN CHIANG

SCIENTIFIC ANALYSES

Applying scientific techniques to the analysis of archaeological pottery helps us gain a deeper understanding of how ceramic objects were made and used in prehistoric societies.

When archaeologists study cultures that produced pottery, initial research focuses on classifying excavated ceramic objects and fragments (sherds) into “types”. A pot is defined by a combination of characteristics related to materials used, shape and decoration. Pots that share attributes form a type. Types are then grouped together into a typology which charts change and variation of types over time and provides a chronological sequence for a given archaeological site. Pots made in a specific place and time share decorative types and thus represent a local ‘style’. A typology is a useful starting point to help identify where a particular pot may have been made or if it was traded from another production area.

Scientific analyses go beyond typology to give us deeper insight into the choices that potters made during the production of pots–from the initial choice of raw materials (clays and temper) to the techniques used to form, decorate, and fire the final product. Scientific data gained from these analyses, combined with typological and contextual information (in situ evidence at a site), enrich our archaeological interpretations of the potter’s craft by identifying distinctive potting traditions and networks of exchange between communities.

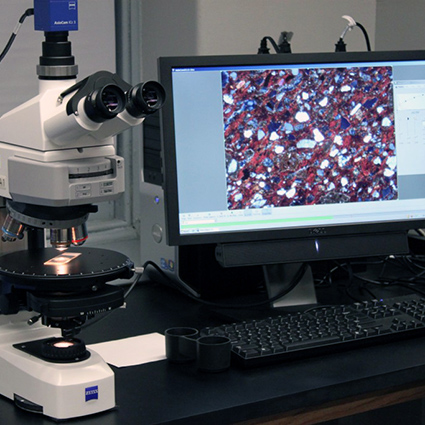

Among the wide variety of scientific techniques applied to pottery analysis, these are currently being used to enrich our understanding of Ban Chiang pots.

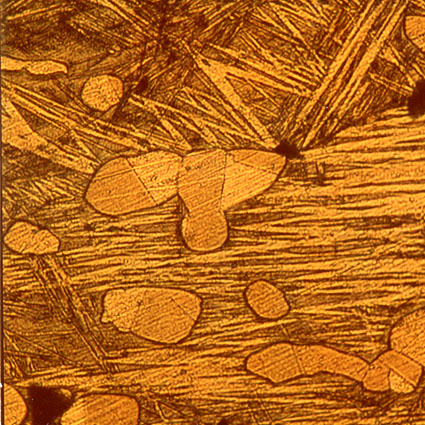

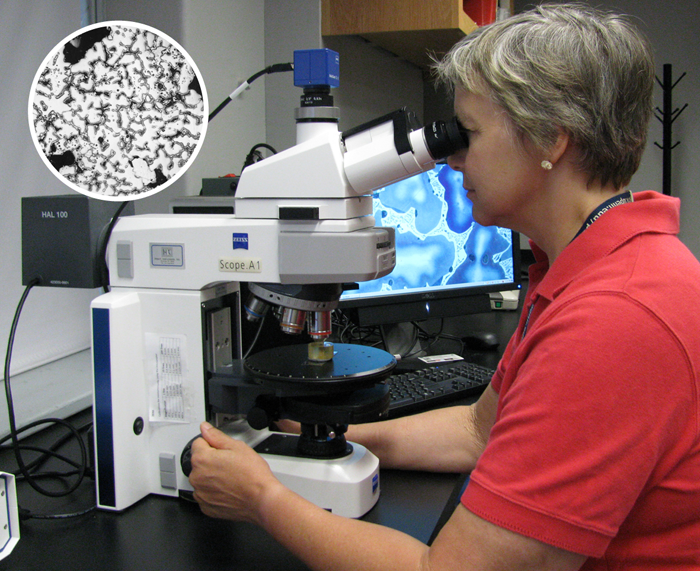

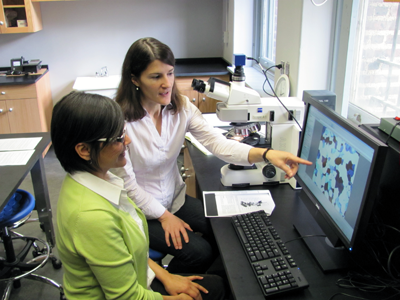

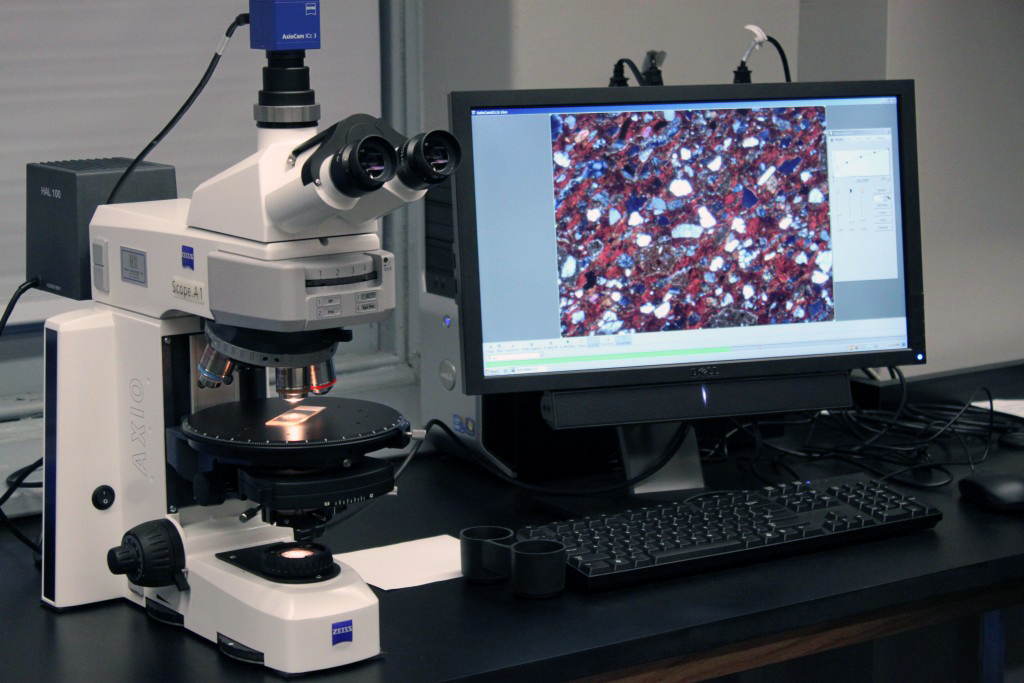

Petrography is an analytical technique that uses polarized light microscopy to examine the minerals and rock inclusions present in a ceramic thin-section. A thin-section is a slice of ceramic, thin enough to transmit light, that is taken from an artifact and mounted on a glass slide. The aim is to match the mineralogy of inclusions to specific geological areas. Petrographic analysis helps identify where ceramic objects were made, thus allowing archaeologists to study networks of interaction between different communities and regions. In addition, ceramic petrography provides data on raw material preparation (i.e. mixing of clays and temper), manufacturing and firing processes by examining the clay groundmass and the shape and sizes of pores. For example, initial petrographic analysis of Ban Chiang thin- sections shows that for some pots, clay was mixed in with rice husks in an effort to prevent shrinkage during drying and firing.

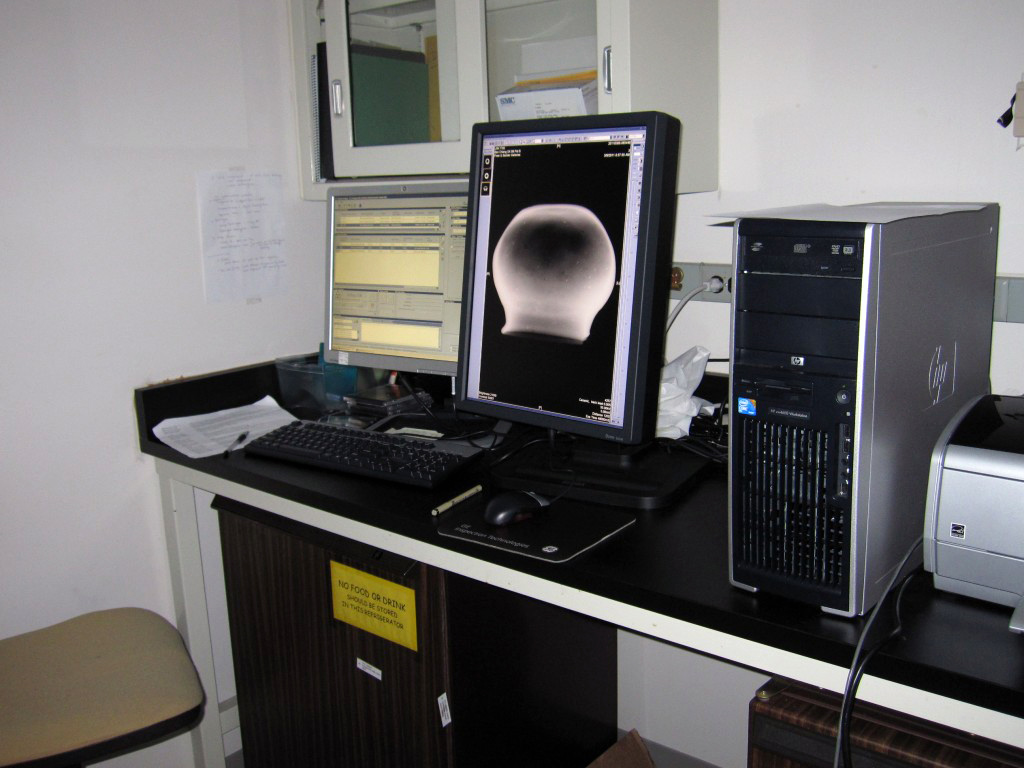

Radiography is a non-destructive analytical technique that reveals the internal structure of objects. Because the techniques ancient potters used to form ancient pots were often masked by the decorative or finishing treatments on their surfaces, radiography provides valuable information about forming techniques not evident to the naked eye. For Ban Chiang, radiographic images obtained with computed radiography helped identify those pots which were made by a combination of techniques, for example a lower body made out of a molded slab and an upper body made of superimposed coils.

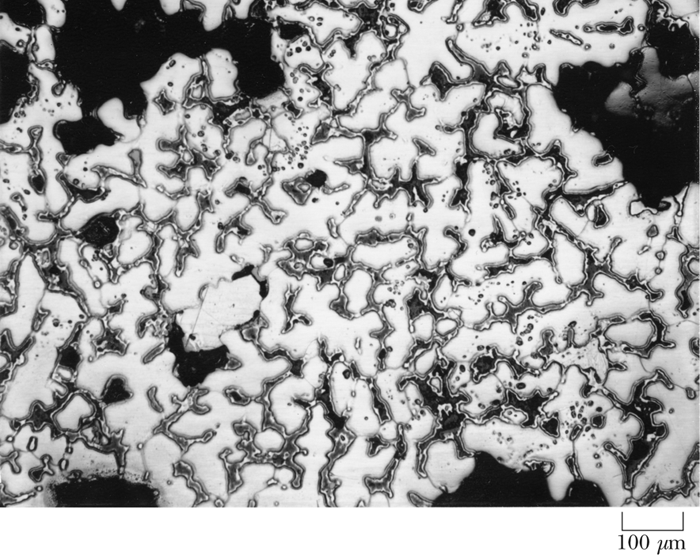

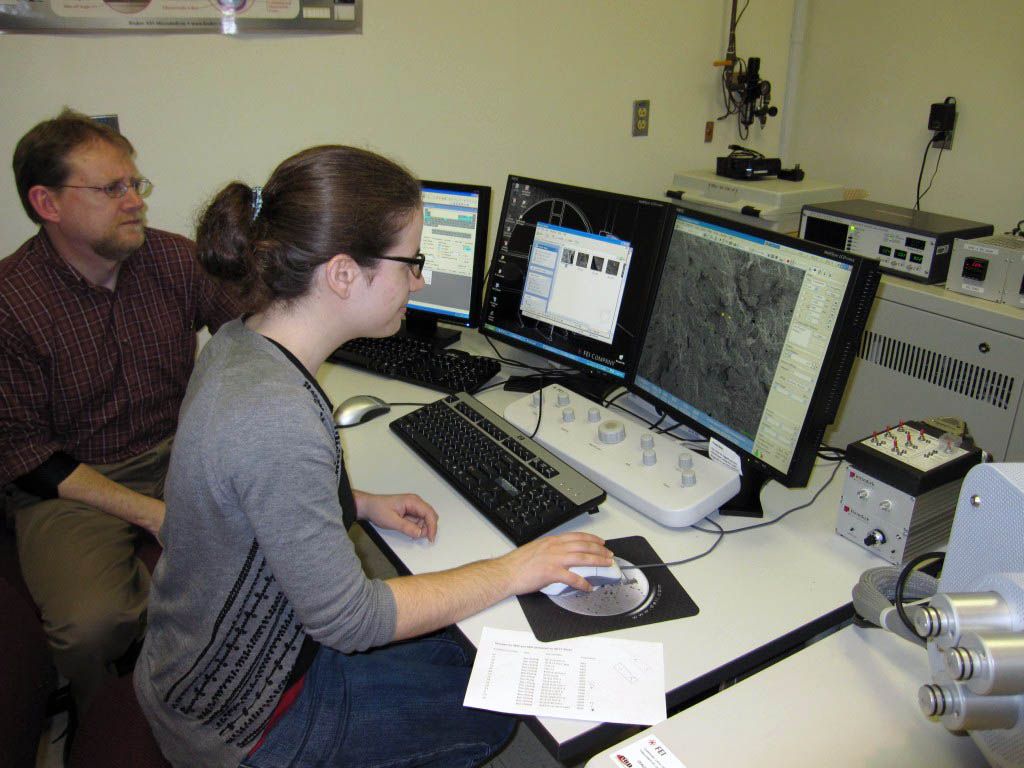

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) uses a beam of electrons to gain information about a ceramics sample at very high magnification. With EDS (energy dispersive spectrometer) capability, it also provides information about elemental composition. When pots are fired above ca. 900oC, processes of melting (sintering) and fusion (vitrification) start to happen. In sintering, the clay particles begin to stick to each other and proceed to melt and fuse with rising firing temperatures. The fusion stage or vitrification stage brings about a loss of porosity and a densification of the clay body. In the case of Ban Chiang pots, SEM-EDS was used to help identify specific ceramic inclusions, examine slip and paint layers, and revealed that clay particles did not start to melt during the firing process, confirming that Ban Chiang pots were low fired.

Portable X-Ray Fluorescence (pXRF) is a nondestructive technique used to analyze the elemental composition of materials applied to the surface of pots, such as slips and paints. To date, a small sample of Ban Chiang pots with painted decoration have been analyzed to acquire information about pigments used to produce different colors.

ISEAA

21ST CENTURY DIGITAL ARCHIVE

The year 2015 marked the start of our 21st Century Digital Archive Initiative for data, images and records from excavations at Ban Chiang and related sites.

In the 21st century, establishing a living digital online archive is becoming the best-practice goal of a modern archaeological program. Such an archive, when carefully developed and curated, can contribute to knowledge in perpetuity: original archaeological field data, photos, and other documentation can be digitized, supplemented with ongoing research data and analyses, then re-studied and re-examined as new questions are asked by future scholars. In the age of international collaborative scholarship, a modern online platform is also a must to make archival content accessible, searchable, and downloadable by all global stakeholders.

Thanks to generous support from the Royal Thai Embassy in Washington, D.C., ISEAA has taken initial steps toward our goal of a 21st century Ban Chiang digital archive. In November 2015, we introduced an upgrade/expansion of the online Ban Chiang metals database and related online content. Improvements include database migration to new software, a better user interface, addition of data from recent metals studies, and more photo documentation. Our goal is to provide scholars more comprehensive tools and resources to examine the metal finds from four key archaeological sites in northeast Thailand—Ban Chiang, Ban Tong, Ban Phak Top, and Don Klang.

Interpretation of these sites’ metallurgical data is presented in the four-volume monograph in the Penn Museum Thai Archaeology Monograph series: Ban Chiang, a Prehistoric Village Site in Northeast Thailand II: the Metal Remains in Regional Context.

White, J.C., Hamilton, E.G. (Eds.), 2018d. Ban Chiang, Northeast Thailand, Volume 2A: Background to the Study of the Metal Remains, Thai Archaeology Monograph Series 2A. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia. Order here.

White, J.C., Hamilton, E.G. (Eds.), 2018e. Ban Chiang, Northeast Thailand, Volume 2B: The Metals and Related Evidence from Ban Chiang, Ban Tong, Ban Phak Top, and Don Klang, Thai Archaeology Monograph Series 2B. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia. Order here.

White, J.C., Hamilton, E.G. (Eds.), 2019a. Ban Chiang, Northeast Thailand, Volume 2C: The Metal Remains in Regional Context, Thai Archaeology Monograph Series 2C. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia. Order here.

White, J.C., Hamilton, E.G. (Eds.), in press. Ban Chiang, Northeast Thailand, Volume 2D: Ban Chiang, Northeast Thailand, Volume 2D: Catalogs for Metals and Related Remains from Ban Chiang, Ban Tong, Ban Phak Top, and Don Klang. Thai Archaeology Monograph Series 2D, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia. Order here.

Follow these links to see examples of enhanced Metals and Metals-related data:

Establishing a full online digital archive for Ban Chiang will be a large scale, multi-year project. Much remains to be done to integrate other resources that are currently offline. However, the Ban Chiang Project has been laying the foundation for a modern digital archive since the late 1970s coding of excavated data began. Starting with the skeletal data in 2002, the Ban Chiang Project was the first archaeological project in Southeast Asia to begin open-access sharing of project data online, as part of our Southeast Asian Scholarly Website. We have since expanded online access to other resources.

Access all of our current online Southeast Asian Archaeological Digital Resources, including a comprehensive bibliography, skeletal and metals data, and multilingual archaeological vocabulary.

ISEAA is a program partner of the Urban Affairs Coalition (UAC), a nonprofit 501c3 entity. UAC administers funds raised by ISEAA, thus freeing us to focus on research and publication.