Transfer of the Ban Chiang Ethnobotanical Collection to the Academy of Natural Sciences:

Lea Belland (left) with the first transfer batch of Ban Chiang Project’s ethnobotanical specimens to the Philadelphia Herbarium at the Academy of Natural Sciences. Chelsea Smith (right) is the collection manager of the Herbarium.

Year of Botany at the Penn Museum, by Lea Belland

My name is Lea Belland, and I am a graduate student at Johns Hopkins University, currently enrolled in my final semester of the Cultural Heritage Management program. For the past several months, I have been interning in the Penn Museum’s Ban Chiang Project lab, working on the Year of Botany, orchestrated primarily by Dr. Joyce White. This project involves the cataloging and organizing of over a thousand botanical specimens collected in northeastern Thailand during the late 1970s and 1980s. The Year of Botany project is a product of international cooperation mostly between Thai and American professionals from multiple institutions. The goal of this initiative is to create a unique ethnobotanical collection that embodies the intersections between culture, archaeology, and botany in the region of Ban Chiang.

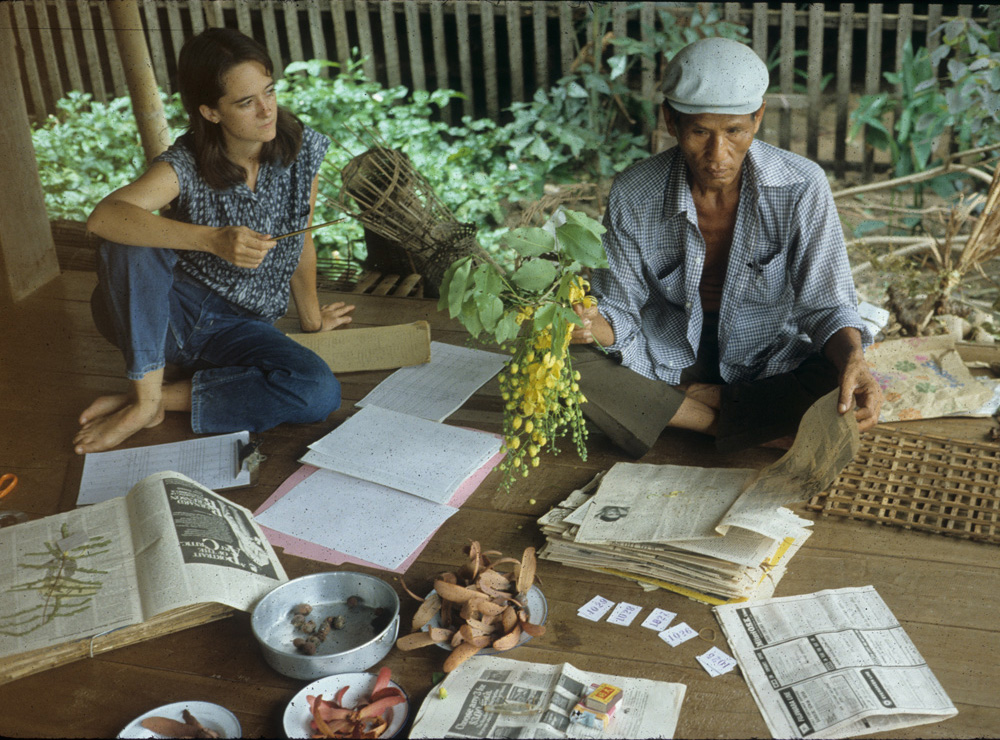

Joyce and Lung Li: Joyce White worked with a Ban Chiang farmer, Li Hirionatha, in 1979-1981 to collect and document plant specimens used for food, medicine, and material culture.

What is ethnobotany?

Ethnobotany is a crucial area of study, as I have come to appreciate over the course of this internship; it gives us valuable insights into historical relationships between humans and their environments. Dr. White’s ethnobotanical investigations at Ban Chiang reveal the deep connections between culture and landscape that have existed and evolved over the course of thousands of years. By thoroughly comparing the modern plant life of Ban Chiang to its archaeological record, we can draw educated conclusions regarding how ancient Thai communities lived and cultivated the land. Through the work of Dr. White and her colleagues, the ethnobotanical resources of Ban Chiang have been thoroughly established, highlighting the potential for scientific investigation in other regions of Southeast Asia. The Ban Chiang Project was instrumental in discovering the early development of plant domestication and agriculture in Thailand, the study of which is relevant not only to Southeast Asia, but also to the international horticultural context. Subsequently, it is essential for us as contemporary professionals to carefully record and make accessible the findings of this and other ethnobotanical collections.

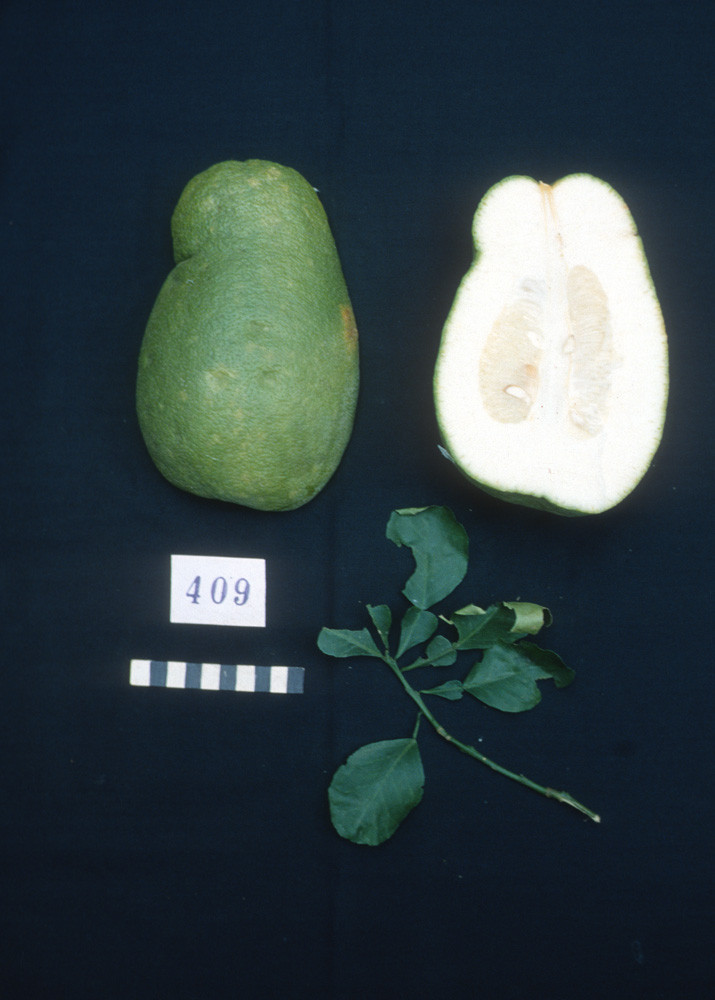

Carpology is the study of fruits, seeds, and nuts. The Ban Chiang collection encompasses a wide variety of carpological specimens as well as flat plant specimens that have been pressed and mounted. Many of the carpological specimens are representative of some of the foundational crops of Thailand and greater Southeastern Asia, like rice, yams, and gourds. These species in particular are important to preserve and study for the information they provide regarding the horticultural development of the Ban Chiang community.

The flat specimens include a myriad of flowers, herbs, and other plant life that are also helpful for deciphering local relationships with the landscape. A major responsibility I have taken on is managing the transfer of the Ban Chiang ethnobotanical collection from the Penn Museum to the herbarium (a place where preserved plant specimens are preserved and used for scientific study) at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. Unfortunately, herbaria have become increasingly rare in modern society due to lack of appropriate funding and research. Thankfully, the Academy’s herbarium is well suited for the long-term care of this collection and will also make it accessible to the public and researchers. This process exemplifies some of the critical aspects of collections management, including proper documentation and preservation, which are essential for maintaining the integrity of any collection.

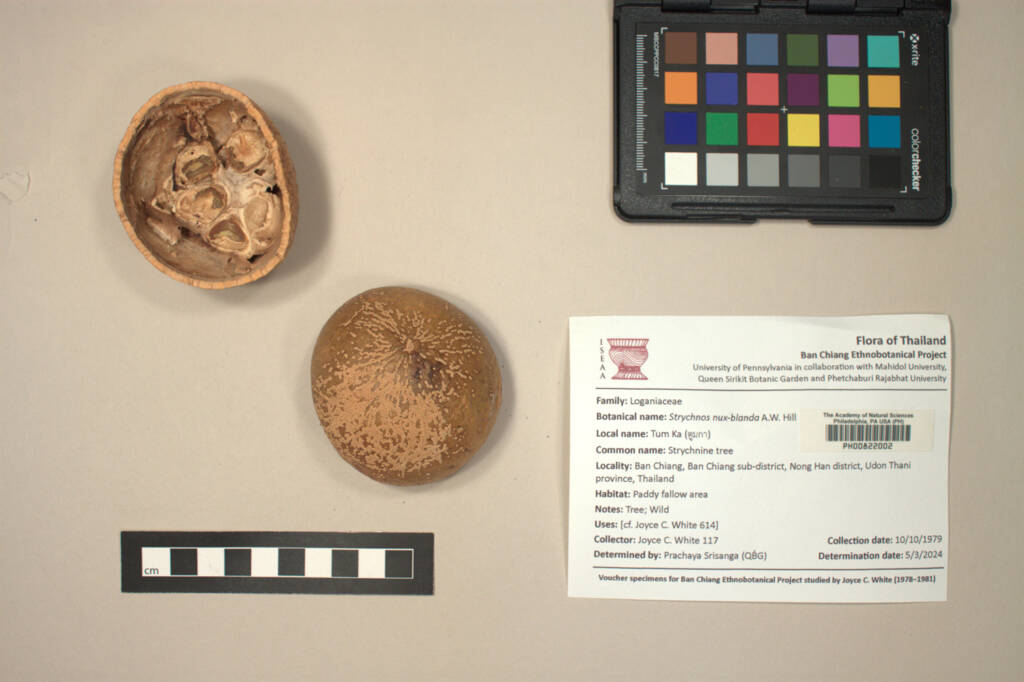

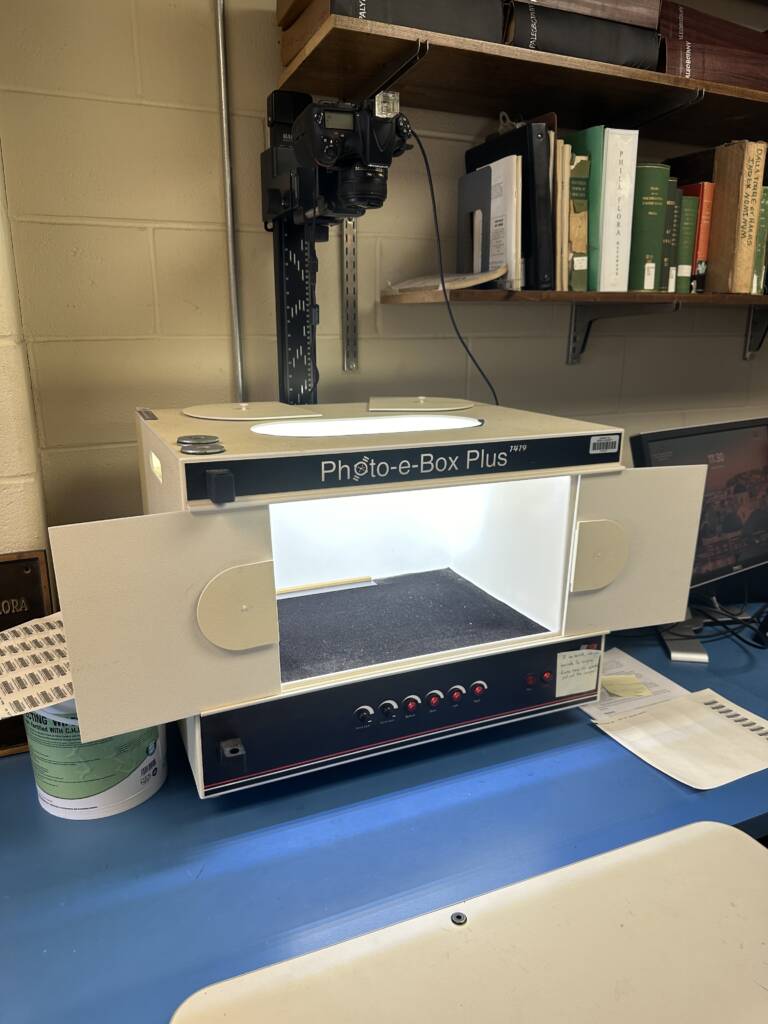

Step by step, my work began with photographing the carpological specimens, which at times required a certain amount of creativity in staging to capture the full detail of each object.

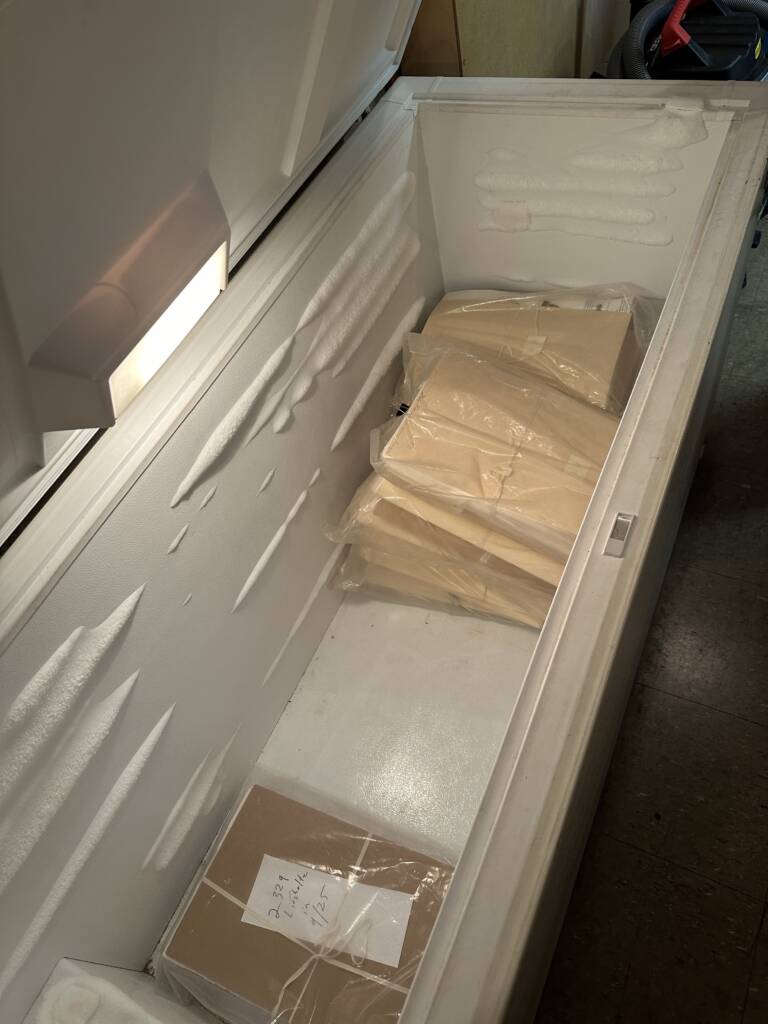

I then entered the photos into the Ban Chiang Project’s’s database, ensuring the collection’s accessibility through detailed, high-quality visual records. Additionally, I have worked on preparing the necessary documentation for the transfer process, which includes spreadsheets with information on each specimen, dates of transfer, and required signatures to ensure accountability. This careful management is important not just for the physical transfer of the objects but also for ensuring that the scientific and cultural significance of each item is preserved. The flat and carpological specimens have specific storage needs, requiring careful handling and a two-week stint in the freezer for each batch to avoid pest contamination, adding an extra layer of complexity to the process.

Recording the data

As I move the collection in batches, I have been ensuring that both the carpological and flat specimens are properly cataloged and stored in the herbarium’s cabinets, of which there is one entirely dedicated to Ban Chiang. This step-by-step documentation is key to successful collections management, ensuring that no item is misplaced or damaged during the transfer. Collections management is not just about preserving items, but also about maintaining a clear and accessible record for future use. This is particularly vital for a collection like Ban Chiang’s, which holds significant cultural and scientific value. One aspect that distinguishes this transfer from others is the need for botanical specimens to be frozen for preservation, a unique requirement not found in every type of collection. At the same time, many aspects—such as detailed documentation, signatures for accountability, and careful handling—are common practices in collections management across institutions. By thoroughly recording each step of the process, including photographic documentation and proper spreadsheet records, I can help ensure the long-term care and accessibility of the collection. I have recently begun to photograph the flat specimens at the Academy, which has been very smooth and efficient so far thanks to their photography setup.

From left to right: Freezer where specimens are housed for 2 weeks in order to kill any potential infestations; herbarium cabinet devoted to the Ban Chiang ethnobotanical collection; photography set up at the Philadelphia Herbarium for flat specimens.