The Ban Chiang excavations revealed a society with distinct differences from the “Bronze Age” society most archaeologists expected.

Production in a rural non-hierarchical society: When bronze artifacts were first excavated at Ban Chiang in the mid-1970s, the prevalent “Bronze Age” paradigm was that only socially-stratified societies had the capability to make objects with this alloy. However, Ban Chiang proved to be an unexpected example of a non-urban, relatively unstratified society that adopted sophisticated early bronze-making technology. And, in the four decades since Ban Chiang bronze was unearthed, archaeologists have discovered similar societies—in Southeast Asia as well as globally—that also produced well-crafted bronze.

Photo caption: BCES 762/2834 is a bronze spear point found next to the body of a 25-30 year-old male (BCES Burial 76) who was buried in a flexed position (the knees were drawn up against the chest of the individual). Evidence suggests the spear point was a “killed” grave good—bent before burial so it was no longer usable for piercing. Early Period (2100-900 B.C.).

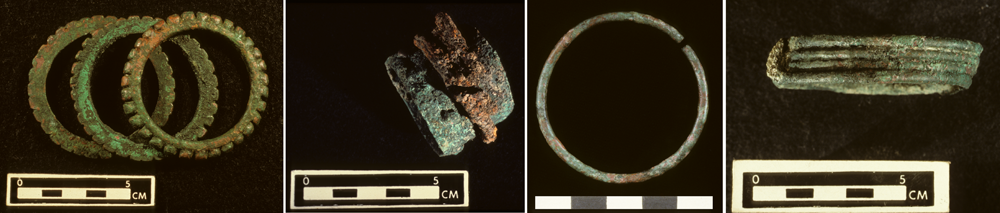

Peaceful use of bronze: The bronze period in this region was a distinctively peaceful one, another divergence from the conventional “Bronze Age” paradigm. At all levels of the Ban Chiang excavations there were few bronze objects that could be used for warfare and an abundance of those that were clearly personal decoration. Other archaeological evidence of warfare is also missing.

New questions about origins: Production of Ban Chiang bronze objects—usually direct casting—was different from production in Europe and western parts of Asia, where forging (hammering) of bronze objects was more common. Ban Chiang bronze technology is most similar to that found in southern Siberia and western China. This similarity raises doubts about previously-assumed origins of Ban Chiang bronze technologies, and gives credence to new explanations of their sources.

New questions about the organization of trade and exchange of metals: The extensive laboratory analysis of metal artifacts from Ban Chiang and other nearby sites has allowed archaeologists to attempt a reconstruction of the trade and exchange of smelted copper-base metal and metal artifacts. Rather than an elaborate system of trade controlled by elites, it seems that production and exchange were controlled by the communities themselves, bringing in smelted metal from several hundred kilometers away and producing and exchanging artifacts made in the villages according to community demand. For more detail, see the link below to the article on Ricardo’s Law of Comparative Advantage.

Read more:

“The transmission of Early Bronze Technology to Thailand: New Perspectives”, by Joyce C. White and Elizabeth G. Hamilton. 2014.

“Metals: Discovery of a peaceful bronze age.”

“The metal age of Thailand and Ricardo’s Law of Comparative Advantage” by Joyce C. White and Elizabeth G. Hamilton. 2021.