By Ella Jewel and Ke Xu

Mew in the Ban Chiang Project office

Mew’s journey to Penn’s Ban Chiang Project started in a village just a short distance from Ban Chiang. Her mother had once visited the site with Mew, sparking her daughter’s curiosity for archaeology early. It was a spark that caught, and by seventh grade, Mew decided to become an archaeologist. In Thailand, though, archaeology is a path few consider; archaeology itself seemed like a distant field, with only one university in the country offering a major in it. But Mew’s parents, especially her mother, recognized her passion and supported her choice.

Mew’s dedication paid off, and she became a curator at the Udon Thani City Museum when she received an invitation for an opportunity to join the Ban Chiang Project at the Penn Museum in the United States in order to document and describe the Ban Chiang ethnographic collection. Mew hesitated. The language barrier felt intimidating, but when she learned about the project’s purpose—preserving Thai culture through careful documentation—she felt a strong sense of responsibility. Here was a chance to to gather knowledge of anthropology and museology she could bring home. And there was another powerful motivation: the opportunity to work alongside Dr. Joyce White, an archaeologist she had long admired. Inspired, Mew took a leap of faith, her fears balanced by a drive to honor her heritage and community.

Mew with Dr. Joyce White

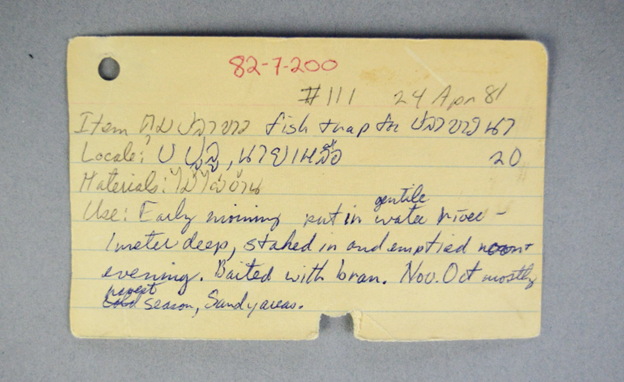

Before starting the project, Mew’s biggest worry was her English. But to her surprise, the real challenge lay in understanding the Thai itself. Many of the items had name tags written in an older, rarely used regional Thai vocabulary, filled with Isaan dialectical quirks and nuances. In Dr. Joyce White’s office, Mew combed through pages of Thai-Isaan and English dictionaries, cross-referenced terms, and even turned to online resources like Esan108.com, where regional knowledge about Isaan culture was cataloged. Her task wasn’t just to translate the name of an object but to find out where it came from, the materials it was made from, and what those choices said about the lives of the people who’d crafted them.

Field note card in the original Isaan Thai

The more she researched, the more Mew felt herself being pulled back through time. Each artifact was like a small key, unlocking memories of her own childhood. She could almost see her grandmother’s hands using the same woven fish traps, weaving baskets, and cooking for the family. She remembered running around with her childhood friends, fascinated by the everyday tools that had once seemed ordinary but now felt precious in the ever-modernizing urban environment. Working on this collection, Mew felt more deeply connected to her Thai heritage and filled with a new pride in her nation. She realized that these objects were not only artifacts; they were memories, bound up with her own identity and culture.

Throughout the research project, Mew has turned to her family for support, relying on their memories and collective wisdom to understand the items’ usage and function. With the help of modern technology and the internet, she can easily connect with her parents, uncles and local assistants, tapping into the invaluable knowledge passed down through generations. When her parents did not have the answers, they reached out to relatives, and sometimes those relatives had to reach out to their village to solve a single question from thousands of miles away. This collaboration reflects the deep sense of community that Thai culture embodies.

Mew’s mother helped connect questions to various knowledgeable locals

Mew is determined to use the skills she acquired abroad back in Udon Thani, and aims to revive interest in age-old traditions, ensuring that future generations can appreciate the beauty and significance of their heritage. Through her work, Mew aspires to create a vibrant tapestry of history, where the past enriches the present and inspires the future.

You can watch her story below: