Year of Botany – Ethnobotany

From 1978–1981, the Penn Museum provided funds to Joyce White, then a PhD student, to assemble an ethnobotanical collection and gather related data on plants used in the vicinity of Ban Chiang village. The intended purpose of the botanical collection was to serve as a reference to benefit the Museum’s archaeological research in Thailand. For various reasons, the field collection remained virtually untouched in the Museum basement since 1981—until 2024.

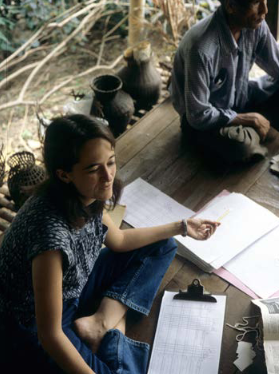

Joyce White compiling the original botanical data in Ban Chiang village, Thailand in 1981 with Li

Hirionatha, a knowledgeable local farmer. Note fishing equipment behind them, purchased for the

Ban Chiang ethnographic collection.

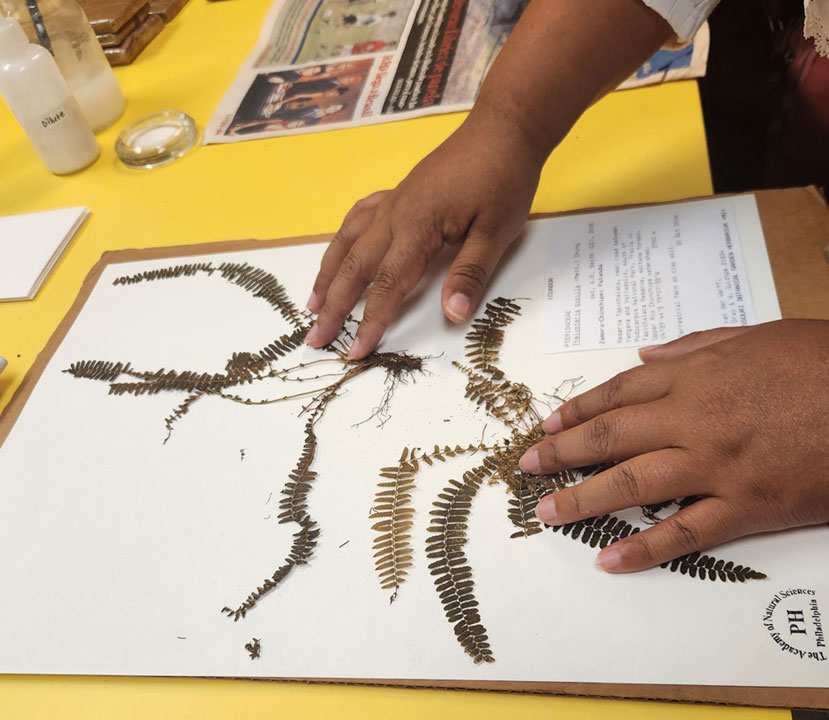

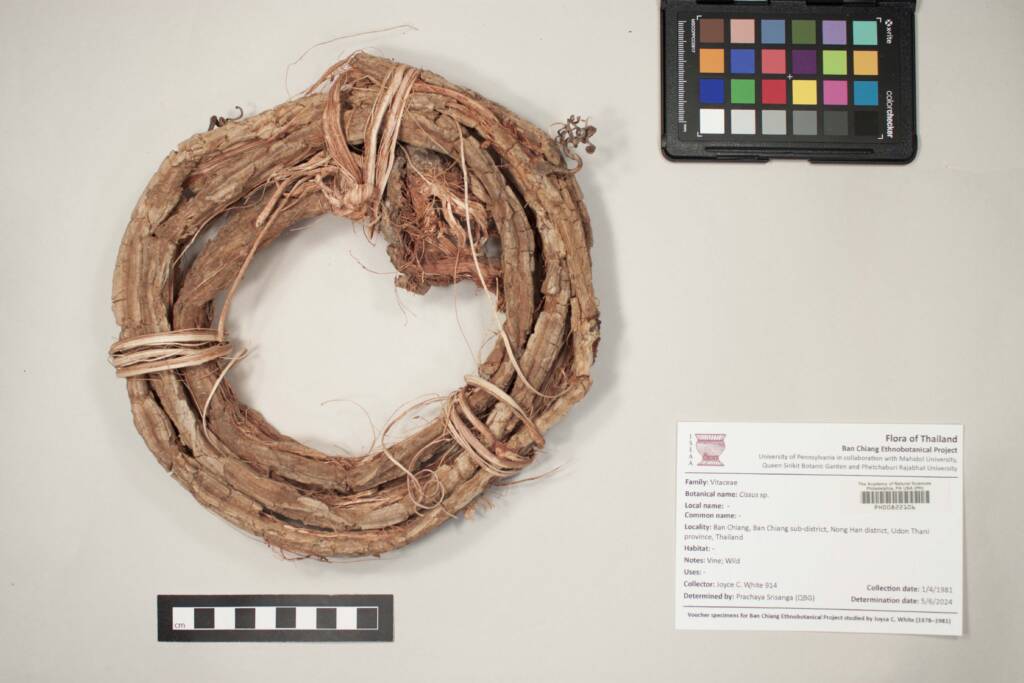

Proper curation of this collection required Thai experts to come to the U.S. to identify each of the more than 1,000 specimens by their scientific names. The specimens needed to be mounted to herbarium standards, and the data had to be digitized, all in preparation for the transfer of the entire collection to the renowned Philadelphia Herbarium at the Academy of Natural Sciences (ANS) in Philadelphia. Dr. Prachaya Srisanga from the Queen Sirikit Botanic Garden identified each specimen by its Latin name through careful analysis and comparison to other collections.

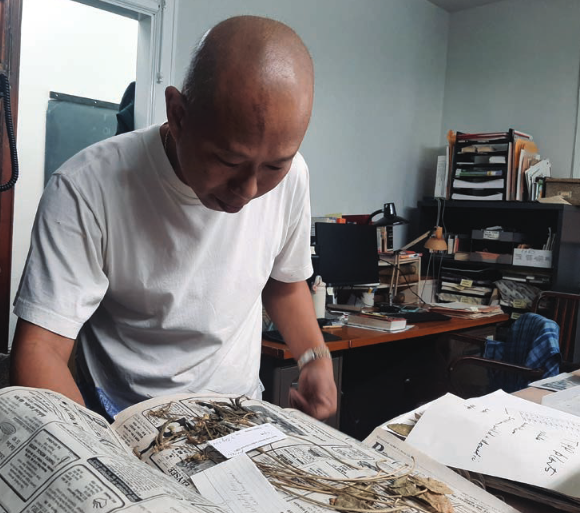

Dr. Prachaya Srisanga identifying botanical specimens in the Ban Chiang Lab at the Penn Museum

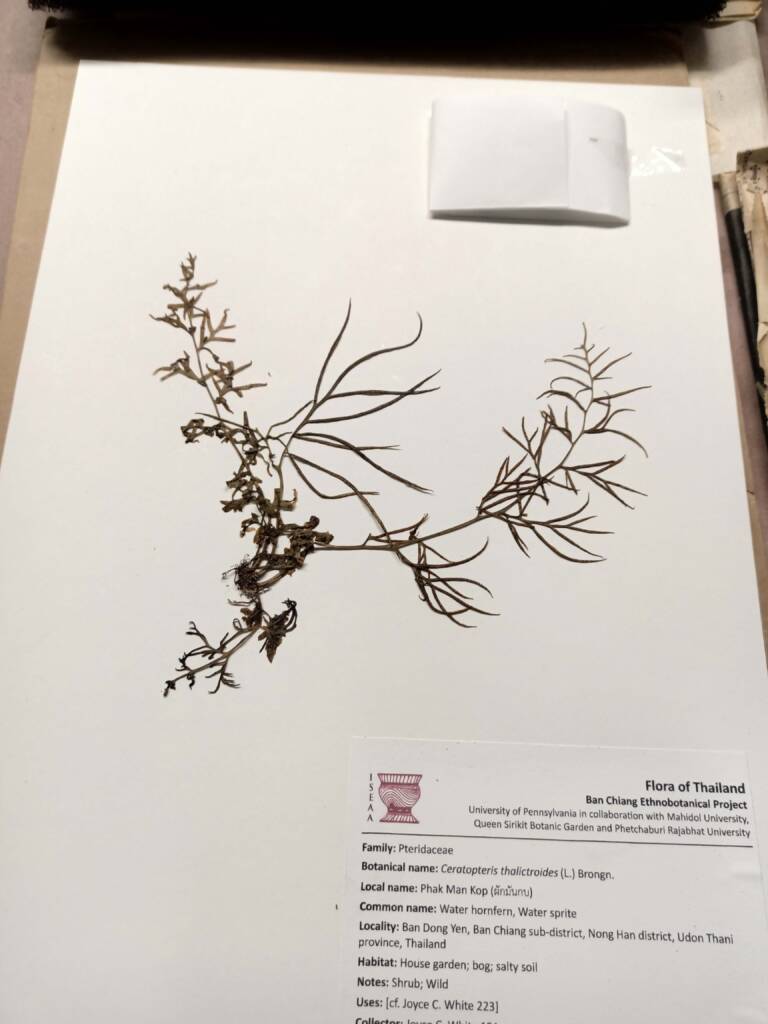

Dr. Varangrat Nguanchoo, an ethnobotanist from Phetchaburi Rajabhat University, compiled the field data into a massive spreadsheet and oversaw the specimen curation and preparation for accessioning at the ANS, with the assistance of Thai interns and volunteers. The field data had originally been handwritten before the advent of personal computers and digital spreadsheets, making this a monumental task. Dr. Varangrat is now preparing a multi-author publication on the collection and its significance to science.

Dr. Varangrat Nguanchoo inspects several of the first mounted specimens from the Ban Chiang ethnobotanical collection.

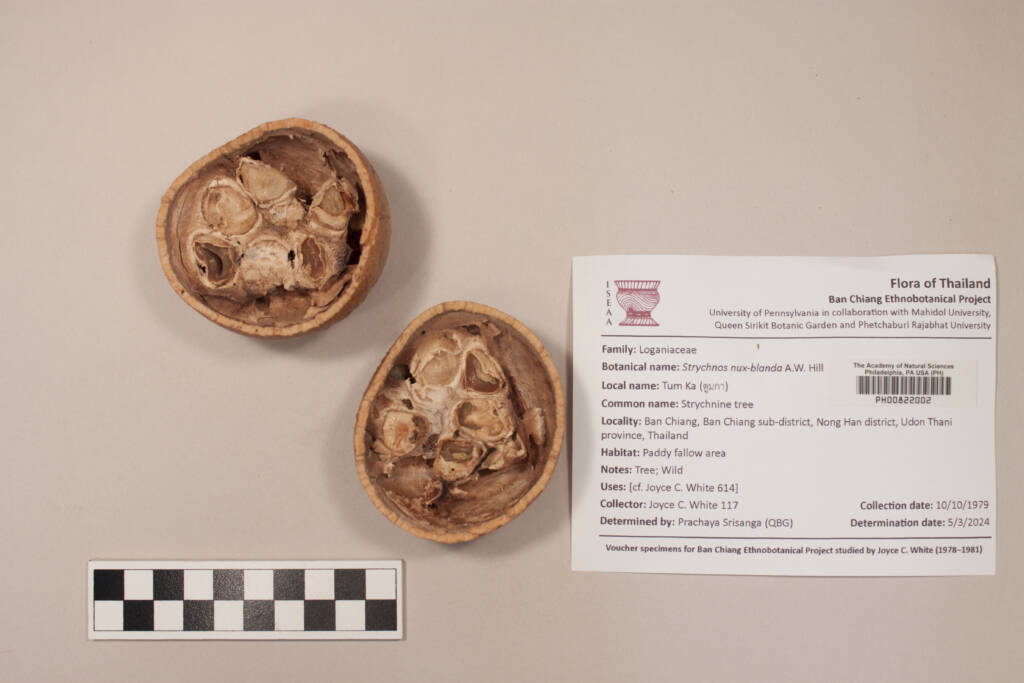

The ANS herbarium manager, Dr. Chelsea Smith, is housing the Ban Chiang ethnobotanical collection in its own designated storage unit. The digital data, including photographs, will be made available online through the Mid-Atlantic Herbaria Consortium (https://midatlanticherbaria.org/portal/). The collection will be accessible for future research across various subdisciplines. For archaeobotanists, the specimens with their individual herbarium voucher numbers can be used to subsample for seeds, phytoliths, pollen, starch, and more. For ethnobotanists, the collection preserves the local wisdom about indigenous plant resources in northeast Thailand, many of which have disappeared. For botanists, the Ban Chiang collection significantly enhances the Academy’s holdings on Thailand and Southeast Asia, with a particular emphasis on economic plants and their various uses.

Lea Belland and Dr. Chelsea Smith with the first batch of herbarium specimens arriving at

the Academy of Natural Sciences.

This is a remarkable and fitting outcome for the important and unique legacy of the Ban Chiang collection.

Check out some of our favorite mounted samples below! Click on an image to see a larger version.

Lea’s Story

My name is Lea Belland, and I’m a graduate student at Johns Hopkins University, wrapping up my final semester in the Cultural Heritage Management program. Over the past few months, I’ve been interning at the Penn Museum’s Ban Chiang Project lab, working on the Year of Botany with Dr. Joyce White and Dr. Chelsea Smith. The project focuses on cataloging and organizing over a thousand botanical specimens from the UNESCO-designated Ban Chiang site northeastern Thailand, collected in the late 1970s and 1980s. This effort is part of a collaborative international project aimed at creating a unique ethnobotanical collection that explores the relationship between culture, archaeology, and botany in the Ban Chiang region.

I

Lung Li, one of the original Thai research guides, plows his field next to Ban Chiang village.

Through this internship, I’ve gained a deep appreciation for ethnobotany, which examines how humans interact with their environment through plants- their cultivation, uses, and even disposal. Dr. White’s work at Ban Chiang has revealed the long-standing connection between the local culture and environmental landscape, showing how ancient Thai communities lived and cultivated plants. The findings are significant not only for Southeast Asia but for global agricultural studies, as Ban Chiang was key to the early development of plant domestication in the region; the area was one of the first to domesticate certain species of rice.

My role in this project involves managing the transfer of these valuable specimens from the Penn Museum to the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. This is important because herbaria like this one are becoming increasingly rare, and the Academy’s facilities are well-suited to preserve these specimens for researchers and the public.

I’ve been responsible for photographing the specimens, entering them into the project’s database, and preparing the necessary documentation for the transfer to their new home. It’s a meticulous process, from capturing detailed images of the specimens to ensuring the paperwork for accountability and tracking.

Additionally, many specimens require special care, like being frozen for two weeks to prevent pest contamination before being transferred. After each batch is prepared, I ensure everything is cataloged and stored in the Academy’s herbarium, where a dedicated space has been set aside for Ban Chiang’s collection. This step-by-step process ensures the integrity and long-term care of the specimens, so they can be used by future generations.